Is Christmas still Christian?

A personal debate sparks a broader inquiry into how Christmas became a secular, shared tradition, and how that speaks to the essence of the holiday.

O.C. Tynes

12/23/20255 min read

Before I discuss this question further I want to make something clear: Yes, Christmas is still a Christian holiday. In fact, it’s the premier Christian holiday; it celebrates the birth of the most important figure in Christianity and the beginning of a new era for semitic mythology. There’s a reason why so many people only go to church on Christmas and Easter. As long as the holiday is called “Christmas”, nobody can deny its connection to Jesus Christ.

That said, I started thinking about this question when I got into a spirited debate about winter in New York City. I referred to the November-January period (when the Christmas markets are open and neighborhoods are decorated with festive props) as the “Christmas season”, and was sternly corrected that I should be calling it the “Holiday season”, since Thanksgiving and New Year’s also play a major part and many people of other faiths don’t celebrate Christmas. While I understood their argument, I pointed out that most of the iconography surrounding the winter decorations explicitly references Christmas – pine trees dressed in lights, red and green color palettes, the animatronic Santa Claus at my local bank, etc. We never reached an agreement, but it sparked my curiosity surrounding our modern understanding of this day.

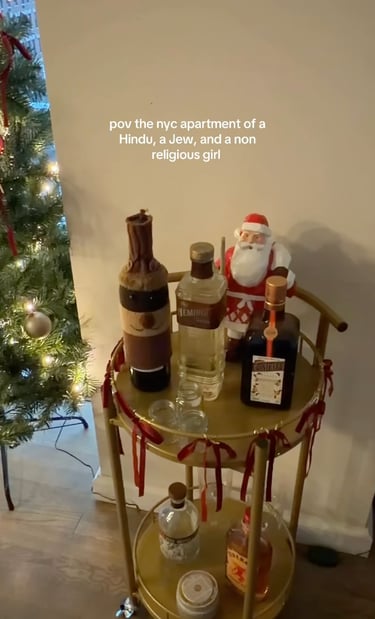

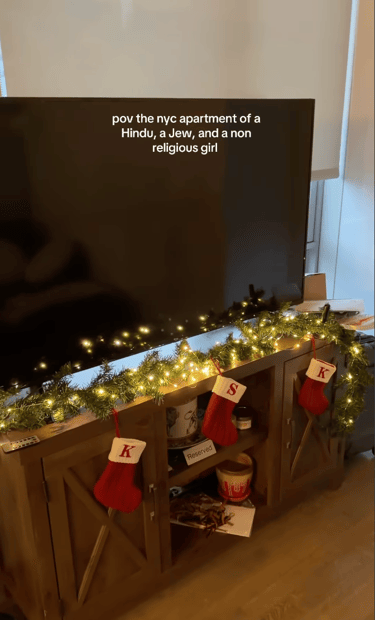

I started thinking about the question again when I was working on an activation with South Asian influencers and saw a reel where one creator showed off her apartment – inhabited by a Hindu, a Jew, and an Atheist – that was heavily adorned with Christmas decorations. An 8-foot tree, stockings on the TV stand, a mini Santa Clause, red bows on furniture; it looked like a luxury unit from a trendy neighborhood in the North Pole.

This reel more or less encapsulated what I was trying to communicate before: my labeling of the November-January period in New York as “Christmas Season” isn’t to ostracize people of other faiths, but an acknowledgment of the secular celebration of the holiday, and how it is still observed (albeit differently) by many non-Christians. Even further, I would argue that the way New York City changes around this time is the perfect example of “secular Christmas”; even my predominantly Muslim corner of Queens is covered in red and green lights by mid November. The public observation of the holiday is about the spirit of giving, lively decor, being with family, slowing down at the end of the year, and of course, Capitalism.

In the original debate, the person I was speaking with claimed that the dominance of “Christmas” during this time was an example of Christian nationalism and religious imposition that should not be encouraged, thus we should use the terms like “the Holiday season” and “Happy Holidays”. She likened its modern ubiquity to how holidays and beliefs were forced onto people when Christianity first began to spread, with Christmas itself being stolen. Ironically, many Christians argue that the public celebration of Christmas is actually an anti-Christian project. They regularly discuss how mainstream society is trying to “take Christ out of Christmas”. There are churches that share guides on how to keep the holiday religiously centered, “Make Christmas Christian Again” shirts on Etsy, and even some who have called to abandon the holiday due to its current connotations.

Personally I see the secular adoption of Christmas as something else entirely: something religious scholars call “Syncretism”. Syncretism is essentially when certain elements, features and components of a belief system are incorporated and/or absorbed into another. It’s a fairly common sociological phenomenon, with one of the most famous modern examples being Santería, the Caribbean religion that blends Yoruba mythology with Catholicism. “Hinduism” as a whole could be seen as one giant example of syncretism, given that the term actually describes a system of various regional beliefs that have borrowed from one another over millennia.

Interestingly, the Christian celebration of Christmas is itself an example of syncretism. Most religious scholars believe Jesus was likely born some time around September or earlier, not December 25th. The reason why this date was chosen is because the most popular Roman festival, called Saturnalia, was observed around this time. While Roman authorities had made Christianity the state religion, this wasn’t an immediate change; in fact, there’s evidence that Saturnalia was celebrated up to a century after Rome’s official conversion to Christianity. Pagan traditions and customs slowly found their way into Christianity with a new set of beliefs and origins – Christmas being the most visible example. Therefore, the establishment of Christmas wasn’t due to religious imposition, quite the opposite: it was the result of a civilization stubbornly keeping its traditions while also adhering to a new belief system.

In the 21st century we see the holiday changing again; this time adapting to a society growing increasingly secular by slowly dropping its religious connotations altogether, and employing a new, more inclusive set of traditions and folklore. Given these changes, I believe the progressives who launched the early 2000s “War on Christmas”, encouraging people to use phrases like “Happy Holidays” and condemning its acknowledgment in diverse settings, were sorely mistaken. The overwhelming presence of Christmas during the winter months isn’t an example of religious intolerance, it’s a testament to the cultural significance of the holiday regardless of one’s personal religious beliefs. Celebrating Christmas in public, non-religious contexts, encourages people of all beliefs to enjoy this time period without questioning if doing so compromises their faith. Furthermore, it’s a natural evolution of the festival, one that has happened in the past.

Studying both the ancient and contemporary practices of “Christmas” reveals an important insight: Western civilization loves its winter solstice holiday, and won’t let it go easily. The winter solstice holiday will continue to evolve with the religious and cultural trends of Western society, possibly outlasting Christianity itself, just as it outlasted the last set of beliefs attached to it. With this in mind, we can all breathe a sigh of relief and acceptance; understanding that the religious attachments to this holiday were never very solid, so we shouldn’t fear them, or fear losing them.

So as one last message, to those of all faiths: Merry Christmas to all, because all should celebrate.

Connect

Your partner in multicultural influencer marketing solutions.

Explore

Engage

info@3rdculturesolutions.com

© 2025 Third Culture Solutions LLC. All rights reserved.